Join our guests Sandra Arnold, MD, MSc (University of Tennessee Health Science Center) and Matthew Kronman, MD, MSCE (Seattle Children’s Hospital) as they discuss the new 2021 PIDS/IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline on the diagnosis and management of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis in pediatrics!

Created by the PIDS Education Committee

Moderated by Heather Young, MD (Arkansas Children’s Hospital)

Edited by Sara Dong, MD (Boston Children’s Hospital)

Dr. Heather Young (moderator): Hello everyone. My name is Heather Young. I am an Assistant Professor of Pediatric Infectious Diseases here at Arkansas Children’s Hospital. And, I’m a member of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society Education Committee. And, today, we are here doing a podcast talking about the very new guidelines for treatment of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis. And, we are here today with two of my esteemed colleagues.

First, we have Dr. Sandra Arnold. She is a Professor at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Pediatric Infectious Disease. She’s actually the Division Chief. And, she is also the medical co-Director of Antimicrobial Stewardship. So, we are very happy to have her with us. And, then, we also have, Dr. Boots Kronman, who is an Associate Professor at Seattle Children’s Hospital. He is also the Associate Medical Director of Infection Prevention and Medical Director of Outpatient Stewardship.

So, Dr. Arnold, you know, we have been waiting several years for these guidelines. And, I was wondering if you could summarize for us what are really the highlights of these guidelines and what all do they encompass.

Dr. Arnold: So, thank you so much for that introduction; and, we’re both really excited to be here. I’m just going to provide a quick summary of the content of the guidelines; and then we will dive into some more detailed discussion of specific points.

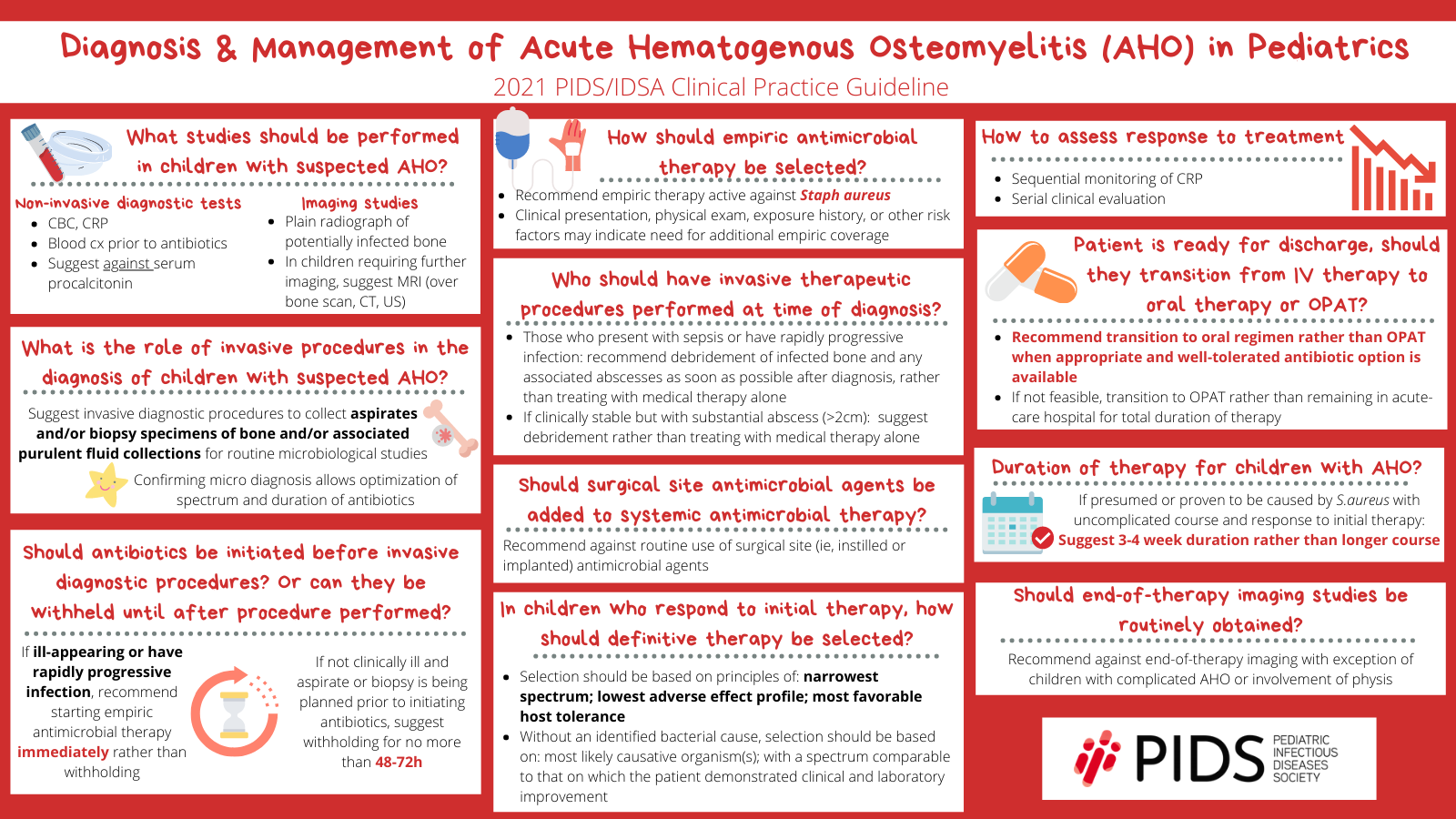

So, the guideline provides a summary of recommendations for both the diagnosis and the management of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis in children. So, the focus is on healthy children, one month to under 18 years, with hematogenous osteomyelitis caused by typical bacteria; typical bacteria meaning S. aureus, streptococci, Salmonella, Kingella, bacteria like that. Bacterial arthritis will be discussed separately in a separate guideline, which is still being worked on and should be released soon.

There are three sections dedicated to the diagnosis of hematogenous osteomyelitis, and also testing to elucidate the etiology of infection. Recommendations are also made around non-invasive diagnostic testing, such as blood tests and diagnostic imaging; as well as, invasive procedures to obtain specimens for microbiologic studies, including bone aspirate or biopsy, or tissue aspirate or biopsy, and specimens from purulent collections.

The section on management addresses timing of initiation and choice of antibiotic therapy, surgical management, choice of definitive therapy, assessing response to therapy, discharge timing, transition to oral therapy, and total duration of therapy. There’s also a section on long term follow-up.

And, so, as you can see, we really run the gamut, all the way from the first clinical presentation, all the way up to the end of therapy, and then long term follow-up of children who have suffered from this infection.

Dr. Young: For then, Dr. Kronman, in your opinion, what’s the most important aspect of this updated guideline?

Dr. Kronman: Yeah, thank you. And, first, of course, thanks for having me; and happy to be here and see you all today. And, thanks, Dr. Arnold, for that high-level overview. I guess I would highlight four things. And, I’m curious if Dr. Arnold would agree, or what she would add here.

But, first, I think the most important thing, about the guidelines, is they exist now! You know, Dr. Young, as you said, these are long awaited; and I really think, finally having these, gives us a place to start, in terms of beginning to standardize care. And, identify best practices and keep getting better over time. So, simply existing is a huge win.

But, in terms of the other three concrete recommendations within the guideline, I would say, first, that the recommendation to obtain diagnostic specimens is important to me. I think it helps us identify the causative agent; and, that will help us to continue to understand the microbiology of acute hematogenous osteo over time. So, that’s pretty important.

Secondly, as has been shown, there’s been great variability in terms of whether kids get transitioned from IV therapy to oral therapy when they’re leaving the hospital. First, you know, shown by Theo Zaoutis, I think it was in 2009 in a Pediatrics paper, and the recommendations in the guidelines now, is to transition most kids to oral therapy at the time of discharge is an important one to me. I think it is the right choice, microbiologically, pharmocokinetically, in terms of side effects from a stewardship perspective. So, that’s a key finding here; or, recommendation I should say.

And, then, thirdly, the recommendation to try and keep the duration of therapy to 3-4 weeks in general, as the sort of minimum. Over time, there seems to have been this creep from, “oh kids need to be treated for 3 weeks”, up to, “well, you know, let’s do 4”, “well let’s do 4-6”. And, I think we can really reign that in a little bit and keep it closer to 3-4 weeks for children with uncomplicated acute hematogenous osteo. And, so that may spare a few weeks’ worth of therapy; which may not sound like much, but certainly is a lot if someone is being woken up to, you know, receive cephalexin every 6 hours or every 8 hours. So, I think that’s an important recommendation here too. Those are the ones I would highlight.

Dr. Young: That’s awesome. Dr. Arnold, do you have anything you’d want to add to that?

Dr. Arnold: Well, I did. I only wrote down two. But I really like the first one, about the fact that we have these guidelines. And, I think it’s incredibly important to standardize care of these kids because there is a huge amount of variation.

But, the two that I did choose, and the one that I thought was most important was the transition to oral antibiotics. I remember when we first started using PICC lines; and, where I trained, we always used oral transition. And, we did not increase our use of PICC lines in osteomyelitis patients, which I was really pleased about. And then, when I came to Le Bonheur, I was very happy to find myself among a group of people who considered oral transition to be the standard of care. But a lot of places, when PICC lines became available, and you didn’t have to put a Broviac into a subclavian vein anymore, they said “Oh, we can just treat everybody with IV antibiotics and then we don’t have to worry”. But, as we know, especially from Theo’s paper, which confirmed what we all knew, which was that, PICC lines are a pain. And, you don’t want to send children home with a PICC line. I wouldn’t want to take my own child home with a PICC line unless it were absolutely necessary. So, I think, I was really pleased that we were all on the same page and felt that this was a really important thing to put in the guideline.

And, then, my second choice, after that, was certainly the limiting duration of therapy. I think we’ve seen duration of therapy creep for sure. Especially with MRSA, because the infections can be really severe, and patients might require multiple visits to the operating room; that, I myself have been guilty of prolonging therapy up to 6 weeks on occasion. Hopefully, appropriately; but actually, since working on this guideline, I personally have been working on getting my durations of therapy down to 3-4 weeks.

Dr. Kronman: Same for me.

Dr. Young: I think there will be many parents who will be very happy to know that, instead of potentially 6 weeks, to go to 3-4 weeks. I mean, that extra 2 weeks, just with the strain of already having a significantly ill child, that’s going to be a little, mental load off of some of these parents, to have a little bit shorter duration.

Alright, so next, I was going to ask Dr. Arnold, if you want to discuss the importance of non-therapeutic tissue diagnosis use, including blood cultures in these children and the importance of getting those.

Dr. Arnold: Absolutely. There’s a lengthy discussion of non-invasive diagnostic testing for osteomyelitis, including lab testing that can help confirm or refute the diagnosis, such as inflammatory markers and CBCs. So, spoiler alert: we are not giving you information on one test that’s going to have sufficient accuracy to rule in or rule out osteomyelitis. That does not exist. The question at hand, however, focuses on etiologic diagnosis of osteomyelitis with blood culture, or bone and tissue cultures, purely for diagnostic purposes.

So, as Boots said a few minutes ago, one of the important things, in this guideline, is getting people to get sample so you can confirm a microbiologic diagnosis. And, this is really important because this allows optimization of the spectrum and duration of therapy. There’s some data to support that children with culture negative osteomyelitis, for example, get treated for longer. And, again, if we want to keep those lengths of therapy down, this is going to go a long way to helping that.

So, for blood cultures, there were two published meta-analyses; and then a meta-analysis that was performed purely for this guideline, and that one included studies from 2005 to 2019. And across these studies, there was a range of blood culture positivity from about 30-40%. Some higher, in more of the 50% range, some a bit lower in the 20s. Blood culture is so simple and easy to obtain; and can allow identification of the etiology within 24 hours without invasive diagnostic sampling. So, you don’t need a sedated procedure. So, the committee was pretty unanimous on recommending obtaining a blood culture prior to initiation of antibiotic therapy in all patients, in though some patients will have negative blood cultures, because the preponderance of benefit is there. And, there’s limited harm. We’re all pretty good at identifying when somebody has a contaminated blood culture; and that’s the main downside of getting a blood culture on every patient.

And most blood cultures will yield pathogens that are relatively easy to grow on our blood culture systems, the typical pathogens that this guideline refers to. Except for Kingella, which is one that won’t grow on blood cultures. And, so, for something like that or in a patient who has a negative blood culture, or in whom you’re worried they’ll have a negative blood culture, invasive procedures to obtain bone or pus specimens for diagnosis, not for therapeutic purposes, we’re not talking about going in and doing an I&D to drain out a large collection of pus to aid in recovery, but more just to identify the etiologic agent, has been made a conditional recommendation. Which means that, the decision that, the group thought that this was a reasonable thing to do; but is influenced by other factors such as feasibility, and patient factors, and obviously the result of your blood culture. So you don’t need to do this if you have a positive blood culture.

But, studies of bone and tissue cultures have been done and, there certainly seems to be an added value beyond blood cultures to doing cultures of the local site of infection. So, the meta-analysis that looked at the studies of additive effect of bone or tissue culture, on top of blood culture, increased the yield of an etiologic agent from 33% to 55%. A separate meta-analysis just looking at the overall yield, so a different set of studies, which is why there’s a different set of numbers, yielded an etiologic agent from 65%. So this shows that bone or tissue aspirate really will increase the likelihood of identifying a pathogen. And, identifying that pathogen can simplify treatments by increasing the confidence in the decisions made, for both the empiric and definitive oral therapies. Excuse me, for both the IV and the oral antibiotics that are given. Hopefully this will drive shorter durations of therapy overall. And, will also help drive that oral transition that we are pushing quite hard on in this document.

Dr. Kronman: I agree with all of that. And, the fact that rates of contaminant blood cultures are about 2%, should really make us feel comfortable that getting a blood culture in every one of these children will not add to diagnostic uncertainty too much, as we try to sort out whether the positive blood culture represents a contaminant or a true pathogen. Especially because most of the time organisms that would be a contaminant would not be a cause of acute hematogenous osteo. So, they can be pretty easy to separate out.

Dr. Young: Awesome. Yeah, in your discussion, of whether or not to go in and get pus or bone from a locally infected area, just reminds me so much, one of my mentors in fellowship, Dr. Jeffrey Starke, would always say, “You got to go where the money is; you just got to go where the money is.” And that’s exactly…

Dr. Arnold: Sutton’s Law.

Dr. Young: Exactly. So, Dr. Kronman, do you mind answering, how long you would be comfortable, after working on these guidelines, with waiting to initiate antibiotics in a well-appearing child, with osteomyelitis, with a planned bone biopsy or surgery?

Dr. Kronman: Yeah of course. And, I’ll tell you, we wrestled with this one, for two main reasons. First, we recognized that we were, there are a lot of children in this country, and their access to care can be quite variable. If you’re in a rural area, very far from a Pediatric Orthopedic specialist who could appropriately perform that procedure, your, the time you might be willing to wait would be different than if you were in a major metropolitan area with hundreds of Pediatric Orthopedists around. So, and, that was the first thing that made it complicated.

And, the second was that there are no great data. It’s not like we’ve done randomized trials where we just let a child where we think has acute hematogenous osteo sit there, waiting, and then do the procedure later, off antibiotics. That just hasn’t happened. So a lot of this is, you know, falls more unfortunately into that group of expert opinion. But, where we landed was, we didn’t want any child to wait longer than 48 to 72 hours.

Certainly for those with more complicated disease, septic appearing, you know, needing vasoactive medications, and so on, we wouldn’t want them to wait nearly as long as even 48 hours. But for the well-appearing child where there is a high suspicion of acute hematogenous osteo, and if you think there’s a high likelihood that a procedure could happen to identify the organism, as Dr. Arnold was saying, in the next, say, 48 hours, it’s reasonable to wait off antibiotics and watch them like a hawk to see if they begin to become more septic-appearing and unstable.

Dr. Young: Dr. Arnold, do you agree? Or, I assume that you do; but, do you have a point you’d like to call out?

Dr. Arnold: I think the thing we wrestled with the most, was how long was OK to wait, not whether or not we should wait. I think most people feel, especially in the hemodynamically stable child, which is a lot of these kids. They come in with fever and pain, but most of them are not that sick. And, a lot of them, they’re not as sick as they were in the early 2000s when we first started seeing MRSA. So, I think, and therefore fewer of them have abscesses that require drainage. I mean we’re kind of getting back to where we were before 2000, where this was a medical disease where we all, everybody just got cefazolin and got better. But, of course, we have the issue of antibiotic resistance. And, we’ve all struggled with what the best way to treat a child is, where we don’t have an organism. And so optimizing our diagnostic studies is really important. And we all know that antibiotics due tend to sterilize cultures. So, I think it was really more just the wording and making sure that we made it clear that if you were worried about the child at all, do not wait to start antibiotics. Because we can always figure it out, it’s just, it’s just more difficult.

Dr. Young: We can easily, if we have culture negative things, give it our best guesses based on our local resistance patterns and the like. So, and that is easier doing than having the morbidity that would come with a child who had delayed treatment of sepsis, so… Awesome.

Going with that, so if you have that sick child, Dr. Arnold, that you’re, it’s going to take a while before you can get a bone biopsy, or before they can get an I&D, what would be your preferred empiric treatment for osteomyelitis?

Dr. Arnold: Right, so, the main recommendation is that every child with hematogenous osteomyelitis has to be empirically treated for Staph aureus. And that is the bottom line.

The question of whether you treat for MRSA as well. So, some places don’t have very much MRSA. And, so, one of things we did struggle with, and the same thing goes for clindamycin when you’re thinking about managing MRSA, do you give empiric vancomycin or do you give clindamycin, is at what level of resistance to the drug. So, you know, for MSSA it’s whether you have resistance to anti-staphylococcal penicillins or if you’re thinking about MRSA and giving clindamycin, at what level of resistance do you need to start thinking about not using that class of drugs. And that’s actually something we faced here because we started seeing a lot of MRSA in 2001 and we got up to a point where 75% of our isolates were MRSA. So, it was actually really easy to decide that we had to empirically treat MRSA. Which I had never seen before I moved here. And, that was great and we had clindamycin and we had 98% susceptibility, so everybody got clindamycin. Some patients who were really sick got vancomycin, as well or in place of. But now, we have 20 to 25% clindamycin resistance and that’s 20 years of steady clindamycin use. And so the committee decided that somewhere in the 10-20%-ish range, again, purely based on expert opinion, because there are no studies, would be a reasonable place to say if you have 10-20% MRSA in your community, you should strongly consider covering MRSA with your empiric therapy. If you have 10-20% clindamycin resistance, the same issue, you should probably be using vancomycin.

The caveat to that is, if you have a rock stable child, you know, we love using clindamycin. Because it’s safer than vancomycin; we don’t have to worry about levels, and are we giving them enough and pushing the levels up high and then causing nephrotoxicity. And, it’s an easy oral transition. So, if you have a really stable child, and I still do this here, I did it last week, I will still give them clindamycin and then monitor them clinically, to see if they respond. Obviously, if we don’t see a response within a couple of days and improvement, and we don’t have positive cultures to help guide that therapy, that’s when you have to start thinking about changing therapy. But we chose that fairly broad range of 10-20% to give people wiggle room. But, even if it’s a bit above that, I still think it’s reasonable to initiate therapy with either cefazolin, or a semi-synthetic penicillin, for MSSA or clindamycin if you’re thinking about MRSA. As long as you can monitor the patient really closely.

And based on their epidemiology and clinical presentation you might cover other organisms, as well. A less than 3 month old, you want to make sure you’re covering Group B Strep. You have a patient who maybe has a sand papery rash that you’re worried about Group A Strep. I saw a lot of Group A Strep osteo in my training. You kind of got to recognize what it looked like; or Sickle Cell patient you’d want to cover for Salmonella. But Staph aureus is, needs to be covered in everybody.

Dr. Kronman: I was just going to add, when we think about that question, what is the rate of clindamycin resistance in our community, are we in that 10-20% range or we higher, we turn to our local antibiogram. And I just was going to make the point that it’s important to remember the local antibiogram does over-represent resistant samples. If there’s a child who has acute osteo due to MSSA and they’re empirically put on cefazolin and they get better they may not get the chance to contribute an isolate. Whereas the child with MRSA who’s put empirically on cefazolin, doesn’t get better, maybe gets a sample and contributes a sample to that numerator and denominator on the antibiogram. And, so, first, just remember that your antibiogram might over-represent resistance.

And, secondly, if possible, locally, some places are able to stratify their antibiogram by type of sample, whether it’s tissue or even from a patient population and that would be ideal. So then if you can say “Oh, we know for sure that among our pediatric osteomyelitis patients our rate of clindamycin resistance is 30% among our Staph aureus; yeah, OK, I guess we better use something other than clindamycin”. So, getting down to what is that number for our community can actually be pretty tricky.

Dr. Arnold: That’s a great point.

Dr. Young: Yes, yes indeed. Alright, so then the next question, is how long do you treat with IV therapy before you switch to oral, Dr. Kronman?

Dr. Kronman: And, see, I think Dr. Arnold had all the hard questions. You know this one is hard only in the sense that we’re like “Well, I don’t know”. I mean, by which I mean, that the data we have are retrospective cohort studies and each of these studies used a different metric. Some said OK we’ll wait until the CRP falls to between 2 and 4. Some said we’ll wait until it’s 50% of the peak. Some said we’ll do it for 2 to 4 days. Some say we’ll do it for 7 days. Some say we’ll do IV until discharge and then switch whenever discharge is ready. So, there’s not been one unifying line in the sand to say here’s the best way to decide when to switch from IV to oral. And, I think we reflect that in the guideline with what we provide in terms of guidance. I think the more important point is please transition to oral before discharge or at the time of discharge. But, whether that’s at 3 days or 5 days, it’s hard to say. Thinking from a limbo mindset, how low can we go, what’s the lowest amount of IV? I don’t think we know that yet. But, I think we do know that it is lower than the full 3-4 weeks. So, I wish we had a better concrete answer to that question, Dr. Young. And, I think, with this guideline, hopefully we can begin generating those data to identify best the transition point. How low can we go in the future.

Dr. Arnold: I think it’s important. It’s one of those things that it’s hard almost to put into words. Because we all know it when we see it. You know, one day you walk in the room, and you look at the child and you go “Oh, you’re ready to go home today”. Because, they’re sitting up and they’re chowing down on their breakfast. And, they’re feeling a whole lot better. And, in some kids that happens gradually. And, in some, they go one day from feeling terrible to the next day feeling great. And, I sort of describe, instead, I’ve never used a particular cut point for CRP. I usually say when the CRP falls off the cliff. ‘Cause it can just sort of, sort of drift down for a bit and then it goes “pitchoo”. And, that’s when they’re clearly getting better. But, it’s also usually the same time that they’re feeling better; they’re starting to get up and move around. The moving around and using their limb can be difficult, especially if they’ve had surgery.

So, back when I trained, before we had to operate on every kid with osteomyelitis, and we gave them cefazolin for 2 to 3 days, and then sent them home to finish 3 weeks of Keflex, it was really easy to tell because they got up and started walking around. It can be a little more difficult in the days, now that more children are having their bones drilled and their periosteum incised. But even so, it’s still a really big part of it. So, I think, you know, everybody kind of has to develop their own way of telling. But, like I said, you know it when you see it. And, it’s different for every child.

Dr. Kronman: And, I think, and this is entirely personal experience, and not from the guideline. But, I think the opposite of what Dr. Arnold is describing is the child who remains on the mesa. You know, stays on that plateau and does not ever fall of the cliff.

Dr. Arnold: Exactly.

Dr. Kronman: Those children, where their symptoms are about the same, their CRP is about the same, for a number of days in a row, those are the ones where I’ve worried about, and certainly at times found, sequestrum or, you know, some other walled-off abscess that ultimately required either a first or a second procedure for drainage. So that’s the opposite of what we’re looking for, is someone who is just stuck. Is how we often we refer to them here, “Oh, that, that poor kid just seems stuck, let’s you know repeat the MRI”.

Dr. Young: Yeah. No, the importance of source control as well, sometimes. I think that’s mentioned very well in the guidelines. That, sometimes if you think your therapy is failing, is it really that you need to achieve good source control. So, completely agree with you there. And, I do, I haven’t used the phrase “stuck” before, but I think I’m going to incorporate that now.

Dr. Kronman: Please do.

Dr. Young: Yes.

Dr. Kronman: Feel free, it’s all yours.

Dr. Arnold: Yeah, and, your point about source control is, you know, we had a surgeon on the guideline committee, which was incredibly important. Because, you know, we’re never in the OR looking and seeing what’s there. And, it was just really great to have somebody who had that, that perspective, to help support a lot of the things that we were saying, that sometimes we get into conflict with our surgeons over. So, that was very helpful. And, I think a lot of that information comes from him, Dr. Copley.

Dr. Young: It did, when I was looking at these guidelines, seeing the multi-disciplinary aspect of these guidelines, it really heartened me a bit. That, like alright, this is something I can also take to my orthopedic surgeons and something they can feel like that there was some of their society’s buy in as well. I think that will help. I mean it’s an interdisciplinary field, in general, as well; I mean there’s the pediatric hospitalists, etc. that we have these guidelines that we can all share amongst each other. I think that that is excellent and that there’s buy in from all of these different specialties into.

So, kind of summing up, is there any last things that you all have to say, or anything? Other than, for me, I’m just very happy that they’re here.

Dr. Kronman: I think that that’s what I was going to say. I don’t remember the gestation period of elephants or whales or other gigantic mammals, but it’s at least this long. Yes, so I think we’re all, we’re all ready for these to be born. And, then, we can fix them. You know, I’m sure they’re not perfect and I’m sure we’ll identify issues that need to change. And, we won’t find them until we start using them and trying to, to figure out what they are.

Dr. Arnold: I completely agree. Just happy that it’s going to be out there. I think it’s really important for people to remember that they are just guidelines. And, we tried to base it as much on evidence as possible. But, we also knew going in that there wasn’t going to be, you know, there weren’t going to be 20 RCTs to support the questions that we had. And, so people have to recognize that there’s a lot of nuance to this and a lot of expert opinion. It’s a large group of experts from all around the country, so that’s really good. And, Canada, where I’m from originally. So, we had Canadians and Americans, and so, and surgeons, and I think it’s been a really great experience for all of us. But, remember, if you want to do something that’s not really outlined in the guidelines, and that’s also OK. That we all make individual clinical decisions for our patients every day.

Dr. Young: And not every child reads the textbook, right. So,

Dr. Kronman: Certainly not.

Dr. Young: Sometimes you have to adjust for the child. So…

Dr. Arnold: Exactly.

Dr. Young: Well, thank you all very much. Hopefully we’ll be speaking again soon.

Dr. Kronman: Looking forward to it.

Dr. Arnold: Talking about septic arthritis.

Dr. Young: Yes. exactly.

Dr. Arnold: Kind of similar.